|

|

Todays Date:

|

Achaemenid Culture and Achievements

Administration of the Empire

To administrate the Empire, the Persian aristocracy and government had to rapidly evolve from a system of tribal feudalism, to a central government capable of administrating an empire of many peoples. Unlike their predecessors, like the Assyrians, who were very strict and controlling with their subjects, the Persian monarchs preferred a more open approach. Often locals were allowed to keep their customs, religion, and tradition. When kings wanted the favor of certain subjects they would make political moves to please their subjects. Examples include Kuroush's treatment of the Babylonians and that he acknowledged their polythiestic religion despite being Zoroastrian. However from time to time the Persians would deviate from these tactics and use harsh measures to keep unruly people in check. During the revolt in Babylon, Khshayarsha I was particularly oppressive in his response. Darayavaush I also harshly punished rebels and impostors who attempted to take the throne, to make an example out of them. These examples were not the general rule of the day. Many cite the Empire's lenience in dealing with subjects as a cause of its eventual downfall.

The main administrative city for general policy was Shoosh. It lay in-between the other capitals and was easily accessible. It also had a well-developed infrastructure, left from the previous civilization of Elam. Although in Darayavaush's time a new Persian alphabet was created, this was used solely for royal inscriptions. Most administrative functions were documented in Elamite, Akkadian, and/or Aramaic, of which we have thousands of tablets surviving.

Social structures and local governments were generally as varied as the people themselves. The Persian monarchs allowed locals, to some extent, to continue using local government structures. As for the Iranians themselves, their society was still presumably feudal. At the time of the Empire's conception, the peoples of Iran were still divided by tribal arrangements, each with their own chief or leader. Usually an overlord would collect tribute and to some extent retain control over local leaders. This feudal system was less prominent, and probably disintegrated as the Persian Empire expanded, came into contact with other peoples, and government diversified. Not much is known of class structure. There was most likely a farmer/peasant class, a religious class, and an aristocracy made up of royalty and distinguished warriors.

Advancements in laws were important to establishing control of the empire. The word for law in Old Iranian was dātā came from dātām and was neuter verb meaning to be set or to be laid down. Two sets of laws were developed. One was local law, based on the traditions and beliefs of each satrapy (like state laws). The other was national law (like federal laws) which generally overrode local law when the two conflicted. The local law was enforced through local councils and judges. National law was enforced by the imperial court. The judges in these courts were generally well-respected, usually Iranian, people selected by the king and his aristocracy. Darayavaush I and his scholars developed the national law based on their ideas and early sources such as Hammurabi. The Bible refers to these as the "law of the Medes and Persians." Of the many laws, one of the most interesting was that for child support. If a man who was not married or engaged to a woman seduced her and got her pregnant he would have to support her until birth. After he does not have to support the woman. But if their child dies from the lack of support, the man would be charged with murder.

Arts and Architecture

The architecture of the Achaemenids was often as colossal as their empire. The Iranians built upon the knowledge of their ancestors which can be seen at sites such as Sialk, Hagmatana (Ecbatana), and Elam where previous civilizations had built large structures. Thus the technical knowledge was available to construct magnificient structures. At Pasargad, the first Achaemenid capital, the ruins remaining give us some idea of what the original palace may have looked like. It was built in a 1.5 mile enclave. The base was built with the same design many nuclear powerplants today use called Base Isolation System. The base at Pasargad was constructed of two pieces. The lower piece was made out of solid stone. The one above was made out multiple pieces of polished stone connected through bits of metal. This made the buildings earthquake prone and resistant up to a richter scale seven. In addition the bases were proportionally wise so as to last on the sandy, light soils. The large base helped to distribute weight more. There are 78 main gates which lead into the palace. The Palace itself is one main hall surrounded by smaller hallways on each of its sides. The many columns which line many walkways in the palace were topped with mythological figures like lion or bullheads and were constructed out of limestone. The floors were generally paved with white marble. The entrances were adorned with black stone that accented their appearance. South of Pasargard lies the tomb of Kuroush, which itself is constructed out of limestone slabs.

Another palace of Kuroush has been discovered in Bushehr, in Charkhab, near Borazjan. The palace at Charkhab is a testament to the amazing feats of the Achaemenid architect. At that time building had to be held in place with mortar. However at Charkab the stones were polished and fashioned to such a skillful degree that they naturally fit and stuck together without mortar. In reality many of the columns were constructed of many pieces, yet the pieces were so skillfully designed that when put together they gave the appearance of a one-piece column. Use of this technique is seen to a lesser extent in Pasargad and Parsa. In Charkhab the columns were contructed out of black and white stone, whereas the columns Parsa and Pasargad were both single-colored. The palace itself was constructed out of two kinds of brick. The inside was unbaked clay, while the outside was made of terracotta. This style of architecture made the palace waterproof and more resistant natural weathering. Archaeologists also believe the architects who constructed the palace at Charkhab used enamel to color and stylize the palace. Enamel had been used by previous civilizations (such as the Egyptians) to glaze pottery. Enamel is formed by melting and fusing flint or silica (in the case of the Achaemenids they used local sands which contain silicon dioxide) with other chemicals such as potash to create a pastable glass that hardens giving a tinted translucent coating. Usually this tint it bluish or greenish, but this can vary and be altered by using different proportions and chemicals in the reaction.

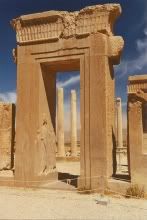

Parsa (Persepolis) was built near a mountainside. Aesthetics played a large role in selection of the location. Iranians liked to build structures that would fit in and accent their surroundings, not stand out painfully. Parsa was built on a 125,000sq. m platform. This platform that made the foundation of Parsa was a 43-sided polygon that almost formed a rectangle. The platform was constructed with blocks of limestones brought in from quarries 25mi to the west. The stones were then hewn so as to be smooth on the edges. This allowed them to stack together well. However the interior of the of the bloocks were left rough and unhewn so they would hold together when placed atop one another without the use of mortar or other adhesives. Small joints made of iron and lead helped keep the stability of the stones. This platform served as a base for the construction of individual units on top of it. Walls of structures built on the platform were generally made of mud brick. The walls were adorned with sculptures of the royal guard, daily life, and floral patterns. Architects filled the insides of the walls with rubble and installed drainage systems. The stairways leading to the platform each had 111 steps which were low enough to allow large caravans and horses to make use of it, yet wide enough to allow ten men to walk on it at once. The entrance to the platform was the Gate of All Nations. Officials from all lands would enter here. Passing south of the Gate of All Nations officials would pass into the Apadana, one of the most magnificient portions of the palace. Its varied decorations, and six rows of six 60ft columns running up and down the 200x200ft square room were designed to dazzle delegates. The Apadana was a reception hall completed during the reign of Khshayarsha I. Directly east of the Gate of All Nations visiting guests would pass into the Throne Hall (also called the Hall of a Hundred Columns). This hallway was a square 230ft on each side. Its walls were filled with images of the kings battling monsters while the hall itself was supported by ten rows of ten columns. Its was completed in the reign of Artakhshathra I and served as a reception chamber. Most of the public audience halls and reception chambers were to the north. To the south lay more of the administrative offices and royal chambers. To the south of the apadana lay the palace of Darayavaush I. The flooring is made of red stone and the walls are constructed with polished black stones, thus naming it the Hall of Mirrors. The palace of Kshayarsha I is twice as large as his father's. To the southeast of the platform lies the treasury. This is where the kings kept gold and tribute. In addition the treaury served as a royal armory.

Artistic development has followed every major civilization and naturally the Persian empire developed an artistic tradition that reflected its status as an empire. Many have suggested that the Iranian tribes were cultureless before the Achaemenid dynasty and borrowed heavily from other cultures. While it is true that the Iranians did use many different artistic styles from many different cultures, it is not true that they had no previous culture, far from it. As the pottery and construction remaining from places like Luristan, Elam, and Sialk show, Iranians had been expressing themselves through art for many years. Not least of which can be seen in the city of Hagmatana, built during the preceding Median Empire. The architecture at Hagmatana shows the columned halls that would become so distinctive of Parsa (Persepolis). Early excavations from Marlik and Hasanlu show evidence of early metal working techniques, which would later play a role in the gold-adornament common of Achaemenid era. Smaller ornamentations where also Iranian of origin, things like silverware, jewelry, and pottery.

The Iranians brought in painters, sculptors, and artisans as well as materials from all across the empire. Royal inscriptions bear reference to gold from Bactria, Ivory from Ethiopia, Cedar from Levantine, and bricks from Babylon. All these elements were directed and utilized in conjunction with the Persian artisans, who worked these elements into a uniquely Iranian style. This reflected the overall status of the Empire which was itself based off the cooperation of various peoples. The Persian's achieved this blend of styles by bringing in many workers and specialists from different nations, having them confer with Persian experts, and overseen by an administrator. One such example is Artatakhma who was the Persian overseer of much of the construction and many of the Artisans. He was handsomely paid at seven and a half shekels per month. The men and women who were gold and silversmiths of the projects were often paid much less, though still well-paid. The women in particular received great wages for that time, far above the average man's. Twenty-seven women were paid one and two-thirds shekels, while five girls were paid one and a quarter shekels. The depictions in many of the structures carry motiffs and symbols. The walls of the many palaces are adorned with images of fierce lions as well as winged, mythological figures and depictions of the royal guard. In the remains at Parsagard we see depictions of the king and his soldiers carved into the walls and the creases are embroidered in gold.

The Empire and its Finances

To sustain and administrate such a large empire, the Achaemenids needed to advance there financial instituions. During the Achaemenid dynasty many advances were made in banking systems, coin minting, and economics. This was no easy task. Already at this stage in history loans, interest rates, currency, and credit were all issues.Most economic policies were administrated out of Babylon, were every single transaction was recorded in the most detail. Business had been carried out in this precise manner for centuries. Babylon was one of the most populous cities, and it experienced a lot of trade.

One of the major advances during the achaemenid dynasty was the development of a standard currency. The Assyrians had experimented with forms of lead, bronze, and copper for minting coins. Later, the Lydians improved the monetary system, coining money in silver more efficiently. Darayavaush continued to develop the monetary system. His mintors studied the Lydian system and developed two coin types: the Daric (gold coins of 98% purity) and the sigloi (silver coins of 90% purity). The exchange rate was set at 1 Daric for every 13 Sigloi. This was corrected from the Lydian rate of 1:13.3 making trade easier. The Sigloi was mostly used in Asia Minor. The Daric was a more universal form of currency. The main minting city was Sardis. The treasury in Shoosh likely minted some coins too.

Money did not have a direct impact on the average citizen of the empire. Most continued to barter. However the standardized monetary system allowed a stable value not only for currency, but also for the products the currency could buy, thus making barter more accurate. The most direct impact came for merchants and bankers. Merchants who bought and sold in large quantities could feel more security in dealing with official money. Likewise bankers would more readily accept official money because of its assured value. It also made trade between merchants of different nations more efficient as the money was standardized at a universal value. In many locations governors and nobility who wanted more autonomy would stockpile the royal currency and mint their money using their reserves of the royal currency as a backing for their money. Sometimes corrupt officials would attempt to mint impure money to stretch the value of their money. Some merchants and bankers who did not pay attention to this were found in very unfortunate circumstances when tax payments were due. Those who did not pay attention to the integrity and purity of their money paid their taxes thinking they had paid the full amount. However, Darayavaush's tax collectors made huge financial charts on tablets, some of which still survive in Shoosh. Here they tabulated everything. From the size and weight, to the type of metal (along with a standardized monetary form, the Achaemenids had developed exchange rates for different metals, thus all payments could be calculated), class of metal (ie white or pure silver), and purity of metal. If after these tabulations the total did not equal the total tax, the faulty individual would often have to pay the discrepancy plus additional fines. If the individual had used official coinage, which was easier to calculate, then he was often given deductions on his taxes. Despite all this, much of the tax was still paid in non-monetary forms. Here the monetary system allowed the Achaemenids, to assign a value for each item received and more readily calculate tax totals.

Taxation itself was a complex issue. Previously taxes were assigned by monarchs as they saw fit. Often all territories were required to pay equal taxes. Darayavaush reformed this process as reorganized his empire. He divided the empire into satrapies, or provinces, which became the tax-paying districts (most of Iran was exempt from taxation). His tax-collectors would survey the productivity of satrapies and accordingly assign taxes. Thus the government was able to garner large amounts of wealth because their taxation system was more reasonable. A satrapy paid according to its wealth and productivity, not a flat tax. However even for its advanced taxation system, the Persian empire still had many problems with overtaxation and its consequences. The taxation was especially burdening for Babylon, whose large size and wealth were reason for higher taxes in the new progressive system of the Achaemenids. Much in the way of precious metals were paid to the government in taxes. This money was often stored, and the achaemenids made the mistake of not spending it. Darayavaush did spend some it, particularly in construction of his palaces and the road infrastructure. However his successor, Khshayarsha spent even less and scraped some of Darayavaush's construction programs. This created a tight money supply. At this time many bankers and wealth loan sharks hoarded any coins or precious metals they could find. As we see in Babylon, many Egytian, Jewish, Phoenician, and particularly Persian, bankers come to take advantage of the economic situation. Thus with a tight supply of money, many people are literally paid in credit (clay tablets that were like credit or debit cards). For the middle-class landowners this became an issue when it was time to pay back the credit. They often turned to loan sharks, such as the Murashu family in Nippur whose records still survive. These loan sharks charged ridiculous interest rates, as high as 40% per annum. During the time the landowner carried out the loan the landowner often got to work the land as collateral. In the end, when many of these landowners could not pay back they were evicted from their property, which was then leased to these same loan sharks! Thus the atmosphere was established for a general revolt by the landowners of Babylon. Although Khshayarsha was able to supress the revolt, it did cost him his war with Greece.

One method to help lighten the burden of taxation, to promote development, and to support the population, the Achaemenid monarchs developed an insurance policy. Subjects were encouraged not only to pay their taxes but to present gifts if they were wealthy enough. Those who paid were given an equivalent insurance, and those who gave gifts additionally were insured twice their value ((more by M.S. Nazmi-Afshar).

However, all said, taxation codes were general more just under the Persians than under previous dynasties. Here we have the example, during Kuroush's time, of Gimillu. Gimillu, a tax-collector, without consent, took many sheep. He also advised his subordinates to rob local farmers for him. When the governor of Babylon asked Gimillu to collect taxes from local shepherds he instead extorted them for "protection" money. Local officials, under building pressure from the public and threats from the satrapal government, brought Gimillu to trial. There were four scribes from the temple present, so we have records of the testimony. Many testified against Gimillu, who eventually admitted to stealing the sheep. He admitted to sending his brother Nadina to rob locals, and even admitted to committing one robbery personally. Gimillu, attempting to lighten his burden, claimed he stole only the youngest lamb, and out of kindness left the other two for the shepherd to recognize the up-coming holy day. Convicted, Gimillu was ordered to pay a fine of 92 cows, 302 sheep, and one pound and ten shekels of silver. Refusing to pay, Gimillu carried out an appeal to the regional satrapal courts. He financed his appeal through more thefts and extortions! The Satrapal court refused to hear the case. However, Gimillu through a contact, raised 5lbs of silver and gave them to influential court members. He also wrote a plea to the judge flattering him beyond ridicule. In the end Gimillu's sentence was reduced to a very light fine and he was again intrusted with power. Responsible for the upkeep of the Uruk temple, Gimillu's character did not change one bit. He refused to pay any taxes or rent to the temple unless he was given better pay and more peasants. However, under the Achaemenids the economy had changed, becoming more open. In the end Gimillu's job did not give him the protection he had expected. His job at the Uruk temple was contracted to one of his subordinates who made a much better bid. Without his job to protect him, Gimillu becomes a fugitive and flees. He disappears, however some of his documents pertaining to his corrupt deals do resurface later on.

The removal of hard-money from the economy presented another problem, this time with trade. The Achaemenids encouraged trade and worked to develop a interconnected economy. The Achaemenids built roads, canals, and financed construction projects that would help bring people of different creeds and nations together to trade. This was successful and the economy began to expand. Naturally, with any expanding economy, the general level of prices rose, and inflation set in. But the tight money supply exasperated this situation, creating devastating inflation during some periods of the empire. The kings often stored vast quantities of precious metals in treasuries in Shoosh. This surplus was not spent and eventually contributed to the empire's downfall. However this was one of the first truly polyglot empires that experimented with such a loose economic system, and despite all the pitfalls the Persian empire expericienced, it nevertheless brought about much trade, economic growth, and was remarkably advanced for its day.

Postal System

One of the many achievements of the Achaemenid dynasty was the development of the Postal system during the reign of Darayavaush the Great. Called Barid, this system was originally developed for imperial use, to help keep the empire stable. Later, it was utilized by other leaders and for business purposes. The postal workers would carry messages via horseback along well-paved and well-guarded road systems. At intervals along the way there were always fresh riders and fresh horses to continue carrying the message without deal. Thus the system was lightning fast for its day.

The Persian Army

For more info on the ancient Iranian military click here

|| Home ||

©Parsa. All rights reserved. Contact Parsa admin at parsa_w@yahoo.com